Wittgenstein’s Language Game: Not Everyone Agrees.

Russell, Putnam, Fodor, Chomsky, Davidson and Pinker.

Ludwig Wittgenstein revolutionised the philosophy of language by challenging traditional theories of meaning and focusing on how language functions in social contexts. In a previous article — From Words to Games: Wittgenstein’s Influence on Modern Linguistics — I wrote about his later work, particularly Philosophical Investigations (1953), which introduced ideas such as language games, forms of life, and meaning through use. These concepts reshaped our understanding of language as a flexible tool embedded in human activities rather than a static system. However, despite his profound influence, Wittgenstein’s approach has faced criticism, particularly from scholars across various fields. not least his friend and mentor Bertrand Russell.

Lack of Systematic Theory

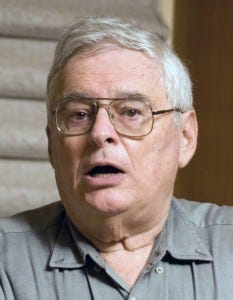

One of the primary criticisms of Wittgenstein’s approach is that it lacks a systematic, comprehensive theory of language. Rather than presenting a structured framework, Philosophical Investigations is composed of reflections and remarks, which some have argued are difficult to apply consistently. Bertrand Russell, who was initially an advocate of Wittgenstein’s philosophy, later expressed frustration with the lack of structure in Wittgenstein’s later work. Russell criticised him for abandoning the logical clarity found in his earlier work, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, for a more ambiguous approach in Philosophical Investigations.

As a counterpoint, I would argue, as many have, that Wittgenstein’s intention was to dismantle rigid theories, not replace them. His approach encourages flexibility, allowing researchers to consider language contextually rather than being bound to fixed theories.

Ambiguity of Language Games

Wittgenstein’s concept of language games illustrates how meaning is context-dependent, but the term itself remains vague. Wittgenstein does not provide a strict definition, leaving us uncertain about the criteria for identifying or delimiting specific language games. Hilary Putnam critiqued this ambiguity, arguing that Wittgenstein’s lack of clarity on what constitutes a language game makes it challenging to apply the concept empirically or methodologically. According to Putnam, this ambiguity prevents a rigorous analysis of language within different contexts.

I would argue that Wittgenstein’s lack of strict definitions allows flexibility, enabling language games to reflect the fluid and overlapping nature of real-world language use. This ambiguity, I suggest, is intentional, allowing for a more realistic view of how language operates in various contexts.

Underestimation of Individual Cognition

Wittgenstein’s focus on language as a social practice led him to downplay individual cognition. By arguing that meaning is grounded in public use, he largely overlooked the role of mental processes in language understanding. Jerry Fodor, a cognitive scientist, criticised Wittgenstein for neglecting internal cognitive mechanisms that contribute to language comprehension. Fodor argued that meaning cannot be fully explained by public criteria alone and that individual mental states play an essential role in understanding.

I think that Wittgenstein’s aim was not to deny the importance of cognition but to critique the idea that language meaning is purely a private, internal matter. By focusing on language as a social tool, Wittgenstein highlighted that shared understanding is essential for communication.

Limited Applicability to Formal Linguistics

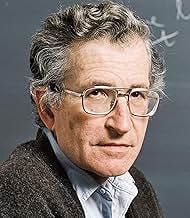

Wittgenstein’s emphasis on context and use has influenced fields like pragmatics and sociolinguistics, but it has had less impact on formal linguistics, which seeks to model language structure independently of specific contexts. Noam Chomsky, one of the leading figure in formal linguistics, criticised Wittgenstein’s approach, arguing that focusing solely on language as a social tool neglects the formal properties essential for grammatical analysis. Chomsky’s theory of generative grammar focuses on the innate structures of language, contrasting sharply with Wittgenstein’s view that meaning emerges from social practice.

It could be argued as a response that Wittgenstein’s emphasis on use and context highlights the limitations of purely formal approaches, which often neglect the practical, lived reality of language. Language cannot be fully understood by isolating it from the social contexts in which it operates and therefore formal linguistics models, while valuable, must account for the dynamic and practical nature of language use.

The Problem of Relativism

Wittgenstein’s concept of forms of life implies that meaning is deeply embedded in cultural practices, raising concerns about linguistic relativism. If each community has its own rules for language, does this make cross-cultural understanding impossible? Donald Davidson, a philosopher of language, critiqued Wittgenstein’s approach for potentially leading to a form of relativism that undermines objective meaning. Davidson argued that communication requires a shared framework and that Wittgenstein’s emphasis on cultural specificity risks isolating communities from one another.

It may, however, be more useful to imagine that Wittgenstein’s focus on forms of life does not lead to relativism but instead underscores the diversity and richness of linguistic practices. Wittgenstein’s concept of family resemblances allows for connections and partial understanding across different forms of life, preventing an entirely relativistic view of language. While language is diverse, it is not necessarily disconnected or incommensurable between groups

Overemphasis on Use at the Expense of Structure

Critics argue that Wittgenstein’s emphasis on use and context overshadows the importance of linguistic structure. For example, Stephen Pinker noted that while context is crucial, the formal properties of language, such as syntax and phonology, also shape meaning and must be acknowledged. Pinker suggested that Wittgenstein’s focus on language as a tool risks neglecting the structural elements that facilitate coherent communication.

The view that structural analysis and social context are interconnected aligns with Wittgenstein’s perspective that structure and use are inseparable. A theory of language codes illustrates this by acknowledging the importance of linguistic structures while emphasising their adaptability to social contexts. It suggests that structural features of language are shaped by and serve specific social functions, supporting the idea that Wittgenstein’s insights complement rather than oppose structural analysis.

Language is more than the sound or signs we produce. Philosophers and linguists push us to question language.

While Wittgenstein’s later work has transformed our understanding of language as a social practice, it has also faced significant critique. His approach challenges static, representational views of language, offering a more flexible, context-dependent perspective. However, scholars like Russell, Chomsky, and Davidson have highlighted limitations in his approach, questioning its systematicity, cognitive implications, and applicability to formal linguistic models. Despite these criticisms, Wittgenstein’s insights remain influential, encouraging linguists to consider the social, fluid, and adaptive nature of language. His legacy endures, providing valuable tools for examining how language functions in the complex tapestry of human life.

©Antoine Decressac — 2024.

As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases

If I remember correctly, Russell praised the early Wittgenstein's philosophy of words being a sort of picture of the world, that they were atomic little bits, and that anything that could not be boiled down to those bits was jargon. Russell's hardheadedness could not appreciate the latter Wittgenstein, which focused more on ways of life and on culture—as well as branching out into other branches that were unimportant to a lot of analytics, such as aesthetics.

I think I prefer Derrida's views of language as opposed to the latter Wittgenstein's, and it's amazing how critics of both typically pull the same card that "it can lead to relativism and what about meaning!”But those are weak attacks on them both. Most well-versed in either will understand that they were not the harbingers of relativism, but that meaning in language was never static or eternally fixed.

1. Formal Grammars and Syntax Trees

Chomsky’s hierarchy of formal grammars (1956) directly influenced the design of programming languages and early natural language processing (NLP) systems. His classification of grammars—regular, context-free, context-sensitive, and recursively enumerable—provided a theoretical framework for parsing human and machine languages.

Example: Context-free grammars (CFGs), which underpin Chomsky’s early work, are still used in compilers and some NLP parsing tools.

Application: These grammars were foundational for symbolic AI and early rule-based machine translation systems like SYSTRAN.

2. Universal Grammar and Language Modelling

Chomsky's idea of Universal Grammar (UG), which posits an innate, language-specific cognitive structure, influenced AI researchers attempting to model human language understanding through structured symbolic rules.

Contribution: UG inspired early knowledge-based systems which tried to encode syntactic and semantic rules in a top-down fashion.

Limitation: UG assumes a rich internal structure not easily captured in algorithms, making it hard to implement computationally without vast hand-coded rule sets.

3. Critique of Statistical Methods

Ironically, Chomsky's strong criticism of statistical models (notably his 1957 review of B.F. Skinner) shaped the debate within AI about data-driven vs rule-based approaches. His scepticism of probabilistic models stood in contrast to what later became standard in machine learning and NLP.

His opposition to behaviourist approaches foreshadowed concerns about black-box models in deep learning, although he also remains critical of today's data-heavy systems.