Michael Silverstein: how language links the micro and the macro

Indexicality, metapragmatics, and why “how you speak” becomes social fact

If you have ever thought “that sounds posh”, “that sounds aggressive”, or “that sounds like TikTok”, you already act like a Silversteinian, even if you have never opened one of his papers. You treat speech as more than words. You hear stance, social position, and a whole theory of personhood moving through tiny linguistic choices.

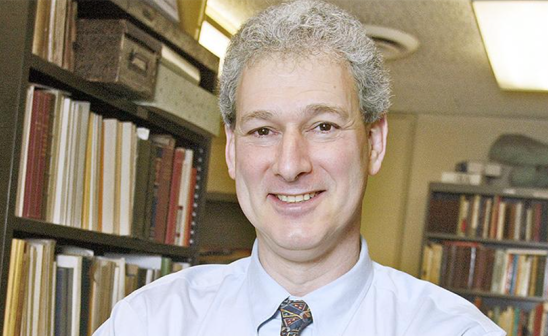

Michael Silverstein (1945–2020) spent his career showing how that happens, with unusual precision and with unusual demands on the reader. His writing can feel technically dense, even forbidding. But the payoff is real: he gives us a way to connect micro details (pronouns, particles, titles, phonology, style) to macro categories (class, authority, authenticity, nationalism) without pretending the macro simply “causes” the micro.

Silverstein’s core claim is not that language reflects society. It is sharper than that. Language is one of the main ways social order gets made visible, argued over, and stabilised. That happens through indexicality, through metapragmatics, and through ideology, all operating at once.

1. The problem he refused to simplify: meaning is not one thing

A lot of linguistics still tacitly treats meaning as mostly referential: words point to things, sentences state facts, grammar composes them. Silverstein does not deny that, but he insists it is only one layer. Alongside reference we have indexical meaning: what an utterance does socially in context.

Take something banal:

“Could you possibly…?”

“Do it.”

“Any chance you could…?”

“Mate, can you…?”

These can aim at the same outcome, but they do not position us the same way. They mark distance or closeness, authority or deference, irritation or warmth, formality or informality. This is not decoration. It is meaning, and it is systematic.

Silverstein’s move is to treat these social meanings as part of linguistic analysis, not as an optional sociological “context” section at the end.

2. Indexicality: the social life of linguistic form

Silverstein helped make Peircean semiotics operational for linguistic analysis, especially the notion of the index: a sign that points by connection to context (time, place, person, stance), not by naming. (Silverstein, 1976)

You see indexicality immediately in “I”, “here”, “now”. You also see it in less obvious places:

accent features that suggest region

/t/ glottalling that suggests a style and a stance, not just a sound

address terms (“sir”, “love”, “mate”) that build an interactional hierarchy

“like”, “literally”, “you know” that manage alignment and footing

Silverstein’s point is that these do not merely accompany meaning. They structure what counts as the situation in the first place.

3. The “total linguistic fact”: the three-way knot you cannot untie

Mid-career, Silverstein names what he thinks counts as the proper object of a science of language in society: the total linguistic fact. Robert Moore quotes Silverstein’s definition as:

“an unstable mutual interaction of meaningful sign forms…” (Silverstein, 1985, cited in Moore, 2021)

The force of that definition sits in what it refuses:

You cannot analyse “forms” without the situations of use.

You cannot analyse use without ideology, because speakers already hold theories about what forms “mean” socially.

You cannot treat ideology as mere opinion, because it shapes practice and therefore shapes what patterns exist to be observed.

This is where Silverstein stops a common shortcut. People often treat “language ideology” as talk about language (complaints, prescriptions, policy). He pushes us to see ideology as a mediating layer inside practice itself. Even when nobody explicitly comments on language, people act as if certain forms are appropriate, inappropriate, educated, rude, authentic, fake, local, foreign, and so on.

4. Metapragmatics: when language carries a theory of its own use

Silverstein’s term metapragmatics names how discourse organises, frames, and calibrates its own pragmatic force. Sometimes this is explicit (“I am joking”, “I am serious”, “Do not take this the wrong way”). Often it is built into the utterance through particles, intonation, quotation, and stance markers. (Silverstein, 2010)

A simple example: reported speech.

“He said, ‘I am sorry’.”

“He was like, ‘Sorry’.”

Even if both report an apology, they frame it differently. The second can carry scepticism, parody, or distancing, depending on delivery. That framing is not outside the language. It is part of the semiotic package.

In his chapter “Metapragmatic discourse and metapragmatic function”, Silverstein sets out the difference between metapragmatic function (how signs organise interaction) and metapragmatic discourse (explicit talk about that organisation). That distinction is important because researchers often measure the explicit and miss the functional.

5. Indexical order: how a feature becomes “a type of person”

Silverstein’s 2003 paper on indexical order is one of his most cited for good reason. It gives us a model for how a linguistic feature moves from correlation to stereotype to social weapon.

A rough way to see the idea:

First-order indexicality: a feature correlates with a group or setting (often unnoticed).

Second-order indexicality: the feature becomes available for evaluation (noticed as “proper”, “rough”, “educated”, “common”).

Higher orders: speakers can stylise it, parody it, contest it, and use it to build identities.

We can apply this to “g-dropping”, to Multicultural London English (MLE) features, to discourse markers, to professional registers, to “customer service voice”, to any patterned way of speaking that becomes culturally legible.

The key idea is dialectical: once people notice and evaluate a feature, they start using it differently. The evaluation becomes part of the phenomenon. That is why Silverstein thinks you cannot treat sociolinguistic patterns as static distributions.

6. What Silverstein changes in method: you cannot stop at counting

Silverstein does not reject quantitative description, but he makes it insufficient by itself. Counts can tell us where a form occurs. They do not tell us what social work the form does in the mouths of real speakers, in real sequences, under real evaluative regimes.

Those who have worked with interactional sociolinguistics (Gumperz) or performance theory (Bauman, Briggs), will recognise the family resemblance: the analytic unit is not the isolated sentence. It is language-in-use, in social time.

What Silverstein adds is a semiotic discipline that stops “context” from becoming a vague word. He forces us to specify:

what counts as a sign form here

what contextual parameters it indexes

what ideological models make that indexing legible

how those models feed back into usage

7. A critical assessment: where the approach bites back

Silverstein is powerful, but there are real costs.

First, readability is a barrier.

He sometimes writes as if the main audience is a small circle of peers with shared technical background. That can make “Silverstein” feel like a badge of initiation rather than an analytic tool. This is not a moral flaw, but it is a practical one. If your concepts cannot travel, they cannot do field-building work.

Second, ideology can get reified.

If we are not careful, “language ideology” becomes a box we put everything into: norms, attitudes, institutions, discourse, identity. That weakens explanation. The fix is to treat ideology as empirically traceable, not as an all-purpose cause. Woolard’s classic framing of ideology as a “bridge” between linguistic and social theory is helpful here precisely because it resists turning ideology into magic. (Woolard, 1994).

Third, higher-order indexicality tempts over-interpretation.

Once we have a model that links a feature to social personae, it becomes easy to tell a story too fast. The discipline we need is deviant-case thinking and careful attention to uptake: do participants orient to the meaning we claim, and how do we know?

Silverstein’s own work points to that discipline, but we still have to apply it.

8. Why he still matters now

Silverstein’s concepts travel unusually well into contemporary problems:

online style shifts and rapid enregisterment

moral panics about “bad English”

institutional language that claims neutrality while indexing power

the way “authenticity” gets produced, policed, and sold

If we analyse language in public life, we repeatedly hit the same question: how does a linguistic detail become a social fact? Silverstein gives us one of the best answers available, even if he makes us work for it.

Conclusion: what you should take away

Silverstein’s lasting contribution is a demanding but usable proposition: if we want to explain language in society, we have to track the interaction of form, context, and ideology, and we have to treat that interaction as unstable and self-revising. That is what makes “language-in-use” more than an observational slogan. It becomes a theory of social semiosis with methodological consequences.

In the next article, it makes sense to stay close to this terrain and turn to Judith T. Irvine, whose work on ideology, differentiation, and sociolinguistic process gives us a complementary route into the same problem.

Judith T. Irvine: Language Ideology as the Making of Social Difference

I have previouly written about Silverstein’s insistence that meaning is not “in” words alone, but in how signs point beyond themselves through indexicality and metapragmatic framing. Irvine is where that claim becomes method. She takes the semiotic insight and asks an anthropologist’s question:

©Antoine Decressac — 2026.

Further Reading

Hall-Lew, L., Moore, E. and Podesva, R.J. (eds.) (2021) Social Meaning and Linguistic Variation: Theorizing the Third Wave. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

A wide-ranging map of how sociolinguists now theorise social meaning, with many points of contact with indexicality and stance.

Perrino, S.M. and Pritzker, S.E. (eds.) (2022) Research Methods in Linguistic Anthropology. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

A methods-focused volume that helps you operationalise “language-in-use” without hand-waving.

Kircher, R. and Zipp, L. (eds.) (2022) Research Methods in Language Attitudes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

A practical guide to measuring attitudes and evaluations, useful when you need evidence for ideological regimes around forms.

Kallen, J.L. (2023) Linguistic Landscapes: A Sociolinguistic Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

A strong introduction to “visible language” and public semiotics, useful for thinking about indexicality beyond speech.

Wilson, G. (2024) Language Ideologies and Identities on Facebook and TikTok: A Southern Caribbean Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

A concise, platform-aware study of how ideologies and identities circulate through digital practices.

Key Silverstein text:

Silverstein, M. (2003) ‘Indexical order and the dialectics of sociolinguistic life’, Language and Communication, 23(3–4), pp. 193–229.

Another great read. I had not known of Micheal Silverstein, but I am glad to know he did not try to reduce meaning.