Karl Bühler and the Functions of Language: From Theory to Use

The shift from static structure to human communication

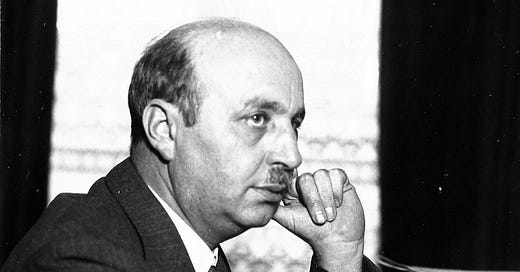

When you think of early linguistics, you might recall Ferdinand de Saussure’s concept of langue and parole or Noam Chomsky’s formal generative grammar. But one figure, working in Vienna during the early 20th century—offered a powerful alternative view of language. Though not leading an organised 'school' in the strict sense, Karl Bühler’s work, shaped by the intellectual environment of Vienna, challenged the idea that linguistics should focus purely on internal structures. Instead, he asked what language is for.

Language in Context, Not Isolation

Bühler developed his ideas during a period of intense philosophical and scientific exchange. In Vienna, thinkers like Wittgenstein and the Vienna Circle were already questioning the role of language in logic, meaning, and empirical observation. But whereas much of the Vienna Circle's work in language was theoretical and epistemological, Bühler’s was grounded in lived communication. He rejected the idea that language could be adequately analysed in isolation from its social and psychological context. Where Saussure emphasised structure—binary oppositions, arbitrary signs, and the synchronic system—Bühler returned the focus on the human act of speaking.

This critical move is not minor. It marks a disciplinary shift: from linguistics as a formal science to linguistics as a human science. In doing so, Bühler’s work anticipates key developments in later 20th-century thought, including pragmatics, discourse analysis, and systemic functional linguistics.

Reassessing Bühler’s Model

Bühler’s most influential contribution is his tripartite model of language use, introduced in his 1934 work Sprachtheorie (later translated as Theory of Language). Known as the “Organon Model,” it proposes that every linguistic sign operates, potentially and simultaneously, on three levels. First, it can express something about the speaker’s internal state, what Bühler termed the expressive function. Second, it can be directed towards the listener to influence their behaviour or attention, this is the conative or appeal function. Third, it can refer to something in the external world, conveying information or representing a state of affairs, this is the representational function. While often reduced to these labels, the model resists simplification. Bühler was clear that these functions frequently overlap and that any attempt to isolate them artificially would distort how language actually works in use.

When someone says, “I’m freezing,” it is easy to code this as 'expressive': a reflection of the speaker’s inner state. But context matters. If said while glancing at a closed window, it becomes a polite directive. If said with a smile in summer, it may be ironic. This complexity resists rigid classification. Bühler understood this. His framework allows overlapping functions, challenging the then-prevailing idea that utterances serve single, isolated roles.

This flexibility distances Bühler’s model from Saussure’s static view of language. Where Saussure limited his scope to langue - the abstract system - Bühler insists that parole, actual speech, is the more fruitful object of study. Unlike Saussure, who treated speech as messy and secondary, Bühler viewed contextually grounded speech as the primary site where meaning is made.

A Functional View of Meaning

Bühler’s model does not just classify linguistic functions; it reframes what meaning is. In his view, meaning is not something contained in words but something realised through use. The ‘organon’—literally, tool or instrument—emphasises this. Language is not a mirror of thought or reality; it is a medium through which human intentions are carried out.

This instrumental view has philosophical implications. It implies that semantics cannot be divorced from pragmatics, that the meaning of an utterance cannot be determined independently of speaker intention and listener interpretation. This stands in quiet but decisive contrast to the structuralist and logical positivist paradigms that dominated early twentieth-century thinking.

Moreover, the emphasis on the speech situation, that is who speaks, to whom, about what, and in what channel, foreshadows later developments in sociolinguistics and contextual theories of meaning. It shares ground with Wittgenstein’s later idea that meaning is use, although it is rarely credited in those discussions.

Influence, But Also Erasure

Bühler’s ideas did not disappear, but they were often subsumed or repackaged. Roman Jakobson, for example, expanded the functional framework to six functions of language, adding poetic, metalingual, and phatic functions. While Jakobson acknowledged Bühler’s work, his model came to overshadow it, particularly in structuralist and semiotic circles. Similarly, Michael Halliday’s systemic functional grammar built an entire paradigm on the idea that language is a resource for making meaning. Halliday’s framework, with its emphasis on ideational, interpersonal, and textual metafunctions, echoes Bühler’s tripartite model but rarely names it.

The marginalisation of Bühler’s work may have stemmed from its interdisciplinary nature. He was as much psychologist and philosopher as linguist, and his work sits uncomfortably in a field that later sought disciplinary purity. In this sense, Bühler’s legacy suffers not from irrelevance but from being too relevant across too many domains.

Why It Still Matters

The central insight of Bühler’s approach which is that language is a tool used by people in social situations remains vital. In today’s climate, where interest in AI, computational linguistics, and formal semantics is growing, there is a risk of returning to decontextualised models of language. Revisiting Bühler reminds us that form and function cannot be separated, and that linguistic meaning is always situated.

Reintroducing Bühler’s work into contemporary discussions is not simply an act of historical recovery. It is a theoretical intervention. It challenges linguistics to remain accountable to real speakers in real contexts, resisting the temptation to abstract language into a disembodied system. The critical lesson here is not that structure does not matter—but that structure alone is not enough.

©Antoine Decressac — 2025.

Further Reading

Bühler, K. (1934). Sprachtheorie. Reprinted and translated as Theory of Language: The Representational Function of Language (1990).

Harder, P. (2010). Meaning in Mind and Society: A Functional Contribution to the Social Turn in Cognitive Linguistics. Mouton de Gruyter.

Nerlich, B., & Clarke, D. D. (1996). Language, Action and Context: The Early History of Pragmatics in Europe and America, 1780–1930. John Benjamins.

Koerner, E. F. K. (2002). Toward a History of American Linguistics. Routledge.

Thank you so very much

Interesting — I suppose that explains the failure of Yale professor Pierre Capretz’s method of teaching French by “pointing.”

https://www.openculture.com/2011/11/french_in_action_cult_classic_french_lessons_from_yale.html