Franz Boas: Language, Power, and the Limits of Cultural Relativism

Pioneer, Linguist, Ethnographer, Controversial Humanist

Franz Boas (1858–1942) remains one of the most significant figures in the history of linguistics and anthropology. Though his name is more frequently associated with cultural anthropology, his influence on linguistics, especially descriptive linguistics and the principle of cultural relativism, helped reshape the field in ways that still relevant today. In an era dominated by racial typologies and Eurocentric hierarchies, Boas provided a rigorous empirical foundation for understanding human diversity through language. He championed fieldwork, rejected sweeping generalisations, and insisted that languages should be studied in their own terms, not through the lens of European grammatical categories.

From Physics to Philology: Boas's Early Path

Trained in physics and geography in Germany, Boas brought a scientific mindset to his later anthropological and linguistic work. His doctoral research on the colour of seawater involved empirical measurements, setting the tone for the precision he would demand in language documentation. After moving to the United States, Boas turned increasingly towards the study of Indigenous cultures and languages, particularly those of the Pacific Northwest. This was not an abrupt switch but a gradual realisation that language was inseparable from the ways people understood and categorised the world.

Descriptive Linguistics: Language on Its Own Terms

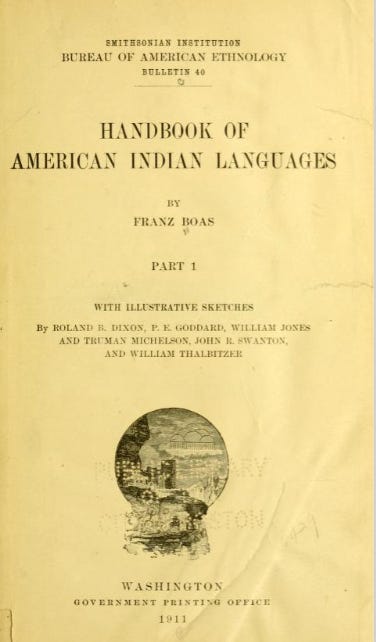

Boas was critical of the comparative philology dominating 19th-century linguistics, which often treated non-Indo-European languages as primitive or deficient. Instead, he insisted on studying each language as a system in its own right. In his 1911 Handbook of American Indian Languages, Boas laid out a new approach: detailed grammatical description based on fieldwork, rather than trying to fit Indigenous languages into existing European categories.

For Boas, language was not merely a tool for communication but a way of perceiving and organising experience. His descriptions of Kwakwaka'wakw, Tsimshian, and other languages were painstakingly detailed, aiming to capture phonetics, morphology, and syntax without importing alien assumptions. Boas encouraged his students and collaborators to transcribe texts, record oral narratives, and analyse speech patterns using the International Phonetic Alphabet. This insistence on rigorous documentation laid the foundation for American descriptive linguistics and inspired a generation of linguists, including Edward Sapir and Leonard Bloomfield.

Cultural Relativism and Linguistic Diversity

One of Boas's most important contributions was the principle of cultural relativism—the idea that each culture must be understood on its own terms, without judging it against Western standards. This insight extended naturally to language. Boas argued that linguistic structures reflect the particular concerns, practices, and worldviews of the cultures they serve. There is no universal hierarchy of languages, just as there is no hierarchy of cultures.

This view clashed directly with the evolutionary models of language popular in his time, which placed European languages at the apex and Indigenous languages at the base. Boas's insistence on parity helped dismantle these assumptions. As he wrote in his Handbook of American Indian Languages (1911), languages previously dismissed as "primitive" are, in fact, as fully developed and capable of expression as any European language. He rejected the notion of linguistic inferiority outright, arguing instead for the intrinsic value and complexity of every language.

The implications were profound. If each language encodes reality in its own way, then translating between languages is not just a matter of substituting words. It requires an understanding of the categories and values embedded in the source language. This idea would later influence the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, although Boas himself never made such deterministic claims.

Language, Thought, and Perception

Boas approached the relationship between language and thought with caution. He rejected the notion that language rigidly determines perception, but he did argue that it guides attention and categorisation. For example, if a language distinguishes between types of snow or modes of motion, speakers may become more attuned to those distinctions in everyday life.

In his essay "On Alternating Sounds" (1889), Boas explored how apparent inconsistencies in pronunciation among Indigenous speakers were not errors but responses to subtle contextual cues. What European observers perceived as carelessness was, in fact, evidence of phonetic nuance and speaker awareness. This was a turning point. Boas showed that variation and context-dependence in language were not signs of inferiority, but indicators of complexity.

This insight continues to matter. In modern linguistics, the attention to context, variability, and phonological awareness that Boas encouraged can still be found nowadays in sociolinguistics, discourse analysis, and cognitive linguistics.

Training a New Generation

Boas did not work alone. He trained and mentored a remarkable cohort of scholars, including Edward Sapir, Ruth Benedict, and Zora Neale Hurston. These students carried forward his methods and expanded his influence across both linguistics and cultural anthropology. Sapir in particular extended Boas's emphasis on linguistic diversity and developed early ideas about the links between language, culture, and thought.

Unlike some of his contemporaries, Boas encouraged direct engagement with native speakers. He valued bilingual informants not simply as sources of data, but as experts in their own languages. This approach fostered collaboration, mutual respect, and a deeper understanding of the languages being studied. His fieldwork model of living with communities, learning their languages, documenting their oral traditions set a standard that many anthropological linguists still follow.

Legacy and Criticism

Boas's legacy is immense, but not without criticism. Scholars such as Dell Hymes (1974) and E. Adamson Hoebel (1954) have argued that Boas's emphasis on detailed empirical description left little room for theory-building within his framework. Hymes, in particular, believed that Boas's reluctance to theorise beyond data collection created a methodological gap that his students had to fill. Others, such as George W. Stocking Jr. (1982), have pointed out that while Boas actively fought against scientific racism, his methods and framing still reflected aspects of salvage anthropology. This approach, dominant in the early 20th century, viewed Indigenous cultures as vanishing and in need of urgent preservation—an assumption that often led to the extraction and archiving of cultural artefacts without full community involvement or consent.

Evidence of this can be found in Boas's own writings and practices. His efforts to collect artefacts and record oral traditions were framed as part of a mission to preserve dying cultures. For instance, Boas frequently referred to Indigenous peoples as facing inevitable extinction due to colonisation and modernisation. While his intentions were to document rather than erase, this framing inadvertently reinforced the colonial narrative of disappearance.

Reading Boa, one can discern a tension in his commitment to cultural relativism alongside his role as a researcher working within institutions that benefited from imperial structures. Though he opposed racist ideologies, Boas’s work was sometimes published and funded by organisations that supported assimilationist policies, such as the Bureau of American Ethnology, which was connected to the U.S. Office of Indian Affairs and its broader mission to assimilate Native populations. For example, the Handbook of American Indian Languages (1911) was published under the auspices of the Smithsonian, whose institutional role included documenting Indigenous cultures as part of a perceived need to 'preserve' vanishing traditions, often in parallel with policies promoting English-language education and cultural assimilation. His participation in World’s Fairs and museum displays further complicates his legacy, as these exhibitions often exoticised non-Western peoples for a largely white public..

Both the pioneering nature of Boas’s work and its entanglement with the colonial realities of his time must be acknowledged. His refusal to rank cultures hierarchically and his advocacy for the value of all languages were radical departures from the norms of his era. Yet his methods and institutional affiliations reveal the limits of early 20th-century liberal humanism. The task today is to build on Boas’s insights while confronting the assumptions that shaped them.

Despite these critiques, Boas's impact is undeniable. He changed the way languages were studied, especially in the Americas. He helped dismantle racialised linguistic hierarchies and established methods that prioritised accuracy, context, and respect for linguistic diversity. His influence is still felt in contemporary linguistics, especially in fieldwork, language documentation, and the ethical dimensions of research.

Why Boas Still Matters

In a globalised world where language extinction is accelerating and linguistic imperialism remains a threat, Boas's work offers a reminder of what is at stake. His belief in the value of all languages, his meticulous documentation, and his rejection of ethnocentrism remain deeply relevant. For linguists, anthropologists, and anyone interested in the human condition, Boas shows how language can illuminate not just what people say, but how they live, think, and relate to one another.

©Antoine Decressac — 2025.

Further Reading

Darnell, Regna (1998). And Along Came Boas: Continuity and Revolution in Americanist Anthropology. John Benjamins.

Stocking, George W. (1982). Race, Culture, and Evolution: Essays in the History of Anthropology. University of Chicago Press.

Boas, Franz (2014). Handbook of American Indian Languages. Cambridge University Press (1911, Smithsonian Institution).

"languages should be studied in their own terms, not through the lens of European grammatical categories" - whoa! This blows my mind, considering the era he was in. I imagine it was quite a radical concept and shows not just an intellect but perhaps a level of empathy in how he saw difference.

This Was amazing! I always tell my students, as a language learner, you don’t pronounce things wrong. Wrong is not the right word. It can not be wrong. It’s the sounds of our languages not fitting.