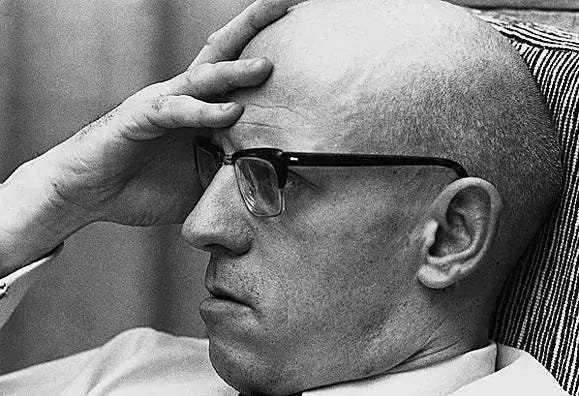

So much has been written about Foucault, by people with a much better knowledge of the man and his work, that my contribution will limit itself to broad headlines on Foucault’s influence on the world of Linguistics. I am also reluctant to write too much as I think that too much has been written about him already. There is almost, particularly in the Anglo Saxon world of academia, a worship of the man which I find unhealthy! This was even more so when I arrived in the UK three months after his death. Do not take me wrong! I met him a few times in my much younger days. I admired him a lot. Foucault is an important character in modern thoughts and some of his ideas have penetrated the world of (theoretical) linguistics.

Michel Foucault, while primarily known as a philosopher and historian, profoundly influenced linguistics by reframing how language is understood within social and historical contexts. Unlike structural linguists, who focus on language as a system of rules independent of social conditions, Foucault treats language as discourse—language actively shaped by, and shaping, society and power relations.

Discourse as Practice

In his seminal work, The Archaeology of Knowledge (1969), Foucault argues against the view of language as merely a neutral medium for communicating ideas. Instead, he proposes discourse as a social practice governed by implicit rules that determine who can speak, what they can speak about, and how they must speak. These rules reflect and reinforce power structures, guiding not just linguistic expression but thought itself. For example, medical discourse not only describes illness but also shapes our understanding of health, normality, and pathology.

"Discourses are practices that systematically form the objects of which they speak."

Episteme: Knowledge and Historical Context

Foucault introduces the concept of the 'episteme' in The Order of Things (1966), defining it as the deep-seated cultural and intellectual framework underlying knowledge production at any given historical moment. The episteme dictates the boundaries of acceptable discourse, determining what counts as truth and knowledge. Foucault illustrates this through historical shifts—for instance, how the Renaissance, Classical, and Modern epistemes fundamentally changed the way humans spoke about and perceived reality.

“In any given culture and at any given moment, there is always only one episteme that defines the conditions of possibility of all knowledge.”

Language, Power, and Ideology

Foucault's analysis extends beyond mere linguistic structures, exploring how power relations are inscribed within language itself. This insight has significantly influenced Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA), a linguistic methodology that investigates how language perpetuates social inequality and ideology. Scholars such as Norman Fairclough and Ruth Wodak explicitly draw on Foucault's theories to examine language in political speeches, media representations, and educational contexts.

Critical Discourse Analysis owes much to Foucault's conception of language as inherently ideological. CDA researchers examine language as an instrument of social control, uncovering hidden biases and power dynamics in everyday communication. For example, studies might reveal how media language shapes perceptions of immigration, influencing public attitudes and policies by reinforcing stereotypes or framing migrants either as threats or as victims deserving sympathy.

Limitations

Despite his influence, Foucault has faced criticism for his broad, interdisciplinary approach. Traditional linguists sometimes argue his work lacks the specificity of formal linguistic methods, such as syntax or phonology. Additionally, critics contend that Foucault’s sweeping historical narratives occasionally oversimplify complex linguistic phenomena.

Lack of Linguistic Precision

Critics, such as Noam Chomsky, have argued that Foucault employs linguistic concepts loosely, lacking the technical rigour expected by linguists. Chomsky notably argued during the Chomsky-Foucault debate (2006) that Foucault's concepts of discourse and language often blur distinctions critical to formal linguistic analysis.

Deterministic View

Some linguists, such as Deborah Cameron, critique Foucault for presenting an overly deterministic view of discourse. Cameron argues that by emphasising how discourse constrains thought and expression, Foucault’s theories risk undervaluing individual linguistic creativity, agency, and the potential for linguistic resistance to dominant discourses (Cameron, 2001).

Historical Specificity

Foucault's analyses are deeply embedded in specific historical contexts, primarily European. Critics such as Teun van Dijk argue that this specificity limits the global applicability of his frameworks, potentially overlooking diverse linguistic environments and practices outside European historical contexts (van Dijk, 2008).

Methodological Issues

Foucault's methods have been criticised by linguists such as Ruth Wodak for lacking systematic empirical procedures common in mainstream linguistic research. Wodak argues that linguists frequently demand replicability, systematic data collection, and empirical clarity, features often absent in Foucault's broader historical and philosophical analyses (Wodak & Meyer, 2001).

Relativism Concerns

Foucault’s assertion that truth and knowledge are constructed through discourse generates significant debate. Linguists like Norman Fairclough have expressed concerns regarding scientific objectivity, questioning how valid linguistic knowledge can be reliably established if all truths are contingent and discursively constructed. Although Fairclough does not explicitly criticise Foucault for lacking clear criteria, he emphasises the necessity for linguists themselves to maintain rigorous methodological standards to ensure validity and reliability, addressing concerns about potential relativism arising from Foucauldian analyses (Fairclough, 1992).

Foucault's Legacy in Linguistics

Foucault's lasting contribution is his insistence that language can never be fully understood without considering its role within larger social structures. By illuminating how language shapes, and is shaped by, power relations, Foucault provides a crucial framework for exploring linguistic practices beyond mere grammar and vocabulary.

Michel Foucault redefined linguistic inquiry by emphasising the inseparable relationship between language, society, and power. His theories continue to inspire linguists to critically evaluate the social dimensions of discourse, challenging the boundaries of traditional linguistic analysis.

©Antoine Decressac — 2025

Further Reading

Fairclough, N. (1992). Discourse and Social Change. Cambridge: Polity.

Foucault, M. (1966). The Order of Things. Translated by Alan Sheridan Smith. London: Routledge Classics.

Foucault, M. (1969). The Archaeology of Knowledge. Translated by A.M. Sheridan Smith. London: Routledge.

Wodak, R., & Meyer, M. (Eds.) (2001). Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis. London: SAGE.

Gutting, G. (2019). Foucault: A Very Short Introduction. OUP Oxford

In debate between Chomsky & Foucault, Noam described the relativistic problem as the creative use of language by the typical 'adult' human being. Which seems to speak to the issue of whether language is an 'innate' aspect of human nature or an 'invented' tool to enhance the prospects of survival? Arguably a tool for making 'allusions' about the unseen nature of reality? Like the way our names are allusions about our own unseen reality? For example, my name is David Bates and when asked if l am David Bates, l say "l am."

To use the author's own words, such is "the power of discourse in shaping reality?" Although l offer the comment that the power of discourse shapes our perception of reality through a psychological 'thought-sight' that overrides the innate power of our biological eye-sight? Hence the philosophical advice "don't think, just look. Don't judge, but perceive?" And R. D. Laing's "we are all in a post-hypnotic trance induced in early infancy?"

Thanks for this - very helpful