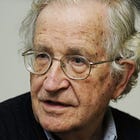

One of the most remarkable things about language is the ease with which we wield it — yet few of us stop to wonder what it truly means to “know” a language. Is it about mastering vocabulary and grammar rules in our minds, or does it involve context and social cues as well? Two influential linguistic concepts offer different perspectives on this question: linguistic competence (associated with the work of Noam Chomsky) and communicative competence (shaped by Dell Hymes). In this article, I explore both ideas, highlighting where they overlap, where they diverge, and why they matter for anyone interested in the workings of human language.

Linguistic Competence: The Grammatical Core

When linguist Noam Chomsky introduced the notion of linguistic competence in the mid-20th century, he revolutionised the field of linguistics by proposing that each of us has an internal, largely subconscious knowledge of our native language’s structure. This knowledge, he argued, goes beyond simply learning words by heart or memorising grammar rules from a textbook. Instead, it involves an innate capacity to generate and understand an infinite number of novel sentences based on an internalised “grammar” unique to the mind. You can read more about Chomsky in my article Born to Speak: Unlocking the Hidden Code of Language.

Born to Speak: Unlocking the Hidden Code of Language

Grammaticality and the Human Mind

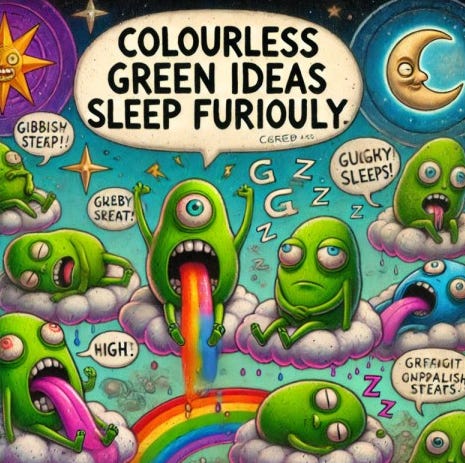

Consider the sentence:

“Colourless green ideas sleep furiously.”

Although it seems nonsensical from a semantic viewpoint, most English speakers recognise it as grammatically valid. Chomsky used this, and other examples like this, to show that linguistic competence concerns the underlying system of rules (syntax, morphology, phonology) that allow speakers to determine whether a sentence is grammatically correct in their language.

For instance, even very young children can quickly sense that “Dog the park to I went” is ungrammatical, despite never being explicitly told the rule that “I went to the park with the dog” follows the standard English word order. This illustrates how linguistic competence is focused on the form of language — its structure — rather than context, purpose, or social nuances.

The Strengths and Limitations of a Purely “Competence-Focused” View

Chomsky’s theory of linguistic competence laid a critical foundation for studying language as a cognitive process. It prioritised the system of rules we unconsciously abide by when we speak or understand language. This approach has enabled remarkable insights into how children acquire language, leading to theories around universal grammar and biological predispositions.

However, critics argue that a competence-only framework does not account for real-world communication, where context, shared assumptions, and cultural norms play a crucial role. For instance, you might have impeccable grammar but still fail to convey your message effectively if you ignore context or social conventions, such as not knowing when to speak or the right register (formal or informal) to use in conversation. This is where communicative competence steps in.

Communicative Competence: The Social Core

Enter Dell Hymes, who in the 1960s and 1970s introduced the idea of communicative competence. Hymes observed that language is not solely a mental grammar system but also a social tool used by actual people in actual conversations. From this viewpoint, knowing how to form a grammatical sentence is only part of the story; we must also know when, where, and how to use those sentences effectively.

Appropriateness and Context

Where linguistic competence is about grammatical correctness, communicative competence is about appropriateness in context. For example, imagine you are at a dinner party, and you want the salt passed to you. Grammatically, you could say, “Pass me the salt.” But if you are in a formal setting or want to appear polite, you might say, “Could you please pass the salt?” or simply, “Salt, please.” Each of these choices, including tone of voice, conveys the same request, but the appropriateness depends on the social context, your relationship to the person you are addressing, and the norms of politeness.

In this sense, communicative competence involves additional layers:

Linguistic Knowledge: grammar, vocabulary, pronunciation.

Sociolinguistic Awareness: understanding the relationship between language use and social contexts.

Discourse Competence: managing extended conversations, turn-taking, topic transitions, and cohesion.

Strategic Competence: knowing how to handle communication breakdowns, rephrase, and negotiate meaning.

Why Communicative Competence Matters

In real-life scenarios, communicative competence often determines whether or not two people truly connect in conversation. Consider travellers overseas who try to speak in a foreign language. Even if their sentences are grammatically perfect, if they choose overly formal words or ignore local customs, they may come across as aloof or out of touch. Conversely, a speaker with slightly imperfect grammar may build strong rapport and be perfectly understood if they use culturally appropriate greetings, gestures, and tones.

Competences in Action: A Balanced Perspective

Although Chomsky and Hymes proposed distinct vantage points, a well-rounded view of language combines insights from both. Indeed, without a solid grounding in the grammatical system of a language, you risk being misunderstood or producing unrecognisable utterances. At the same time, even the most flawlessly constructed sentence can be rendered ineffective or downright offensive if delivered without regard for context, politeness norms, or the shared knowledge base of the listener.

In many modern language-teaching methodologies — such as Task-Based Language Teaching or Communicative Language Teaching — there is an emphasis on speaking and listening in meaningful contexts, rather than simply memorising lists of vocabulary or grammar rules. This approach recognises that genuine language proficiency requires both linguistic competence and communicative competence.

Take, for example, language exams like the IELTS (International English Language Testing System). They do not merely test if you can fill in the blanks with the correct verb form; they also ask you to engage in short conversations, simulate real-life scenarios, and produce connected discourse. These tasks reflect a desire to gauge how test-takers use language dynamically, whether they can adapt to the context, maintain conversation flow, and employ strategies when faced with unfamiliar questions. This is communicative competence at play.

Bridging the Gap for Learners and Enthusiasts

If you are learning a new language or simply fascinated by how languages work, it helps to understand that both theories tell part of the story. Learning grammar, pronunciation, and vocabulary (the hallmarks of linguistic competence) is indispensable. However, to truly become effective in a language, you need to appreciate the social and cultural dimensions of communication.

Observing how native speakers tailor their language to suit different situations, how they use idiomatic expressions, or how they navigate polite requests are all crucial. In essence, you are learning the unwritten social rules that go alongside the grammatical ones. Tuning in to these cues transforms mechanical language use into genuine communication.

Conclusion

Linguistic competence and communicative competence each reveal fundamental truths about language: one draws our attention to the hidden computational systems in our minds, while the other highlights the equally vital social context that shapes how and why we speak. By understanding both, we come closer to appreciating the full richness of human communication, a balancing act between the internal grammar that lets us form sentences and the external social world that gives those sentences meaning.

For anyone enthralled by language, seeing it as both a mental phenomenon and a social tool can be enlightening. It reminds us that language is not simply about “correctness,” nor is it purely about context: it is a rich tapestry woven from both threads. Embracing this complexity can enrich our communication skills, whether we are writing an essay in our first language, learning a second, or simply marvelling at the subtlety and grace of human interaction.

©Antoine Decressac — 2025.

Here are a few books you may find interesting:

The Language Instinct by Steven Pinker (1994)

A classic popular-linguistics text, The Language Instinct takes readers on a tour of how children acquire language and why our brains seem “hard-wired” for grammar. It’s both entertaining and informative, making complex ideas about linguistic competence remarkably approachable.How Language Works by David Crystal (2006)

David Crystal, a renowned British linguist, presents a wide-ranging look at language — from the basic sounds to the nuances of social interaction. This book lays out the foundations of both linguistic competence (the structural building blocks of language) and communicative competence (the social use of language) in a clear and reader-friendly manner.The Language Game: How Improvisation Created Language and Changed the World

by Morten H. Christiansen and Nick Chater (2022)

This more recent publication delves into the interactive and adaptive nature of language. Christiansen and Chater argue that language emerges through improvisation and constant re-invention in social contexts. It’s an excellent illustration of how communicative competence isn’t fixed, but rather evolves through our daily interactions.The Power of Language: How the Codes We Use to Think, Speak, and Live Transform Our Minds

by Viorica Marian (2023)

Published within the last couple of years, Marian’s book explores the impact of bilingualism and language choice on the brain. While its focus extends beyond competence in a single language, it underscores how our linguistic and communicative abilities influence thinking and identity across different social settings. It’s especially relevant if you’re interested in how cultural and cognitive factors intertwine with language use.

What is the actual value of linguistic competence and being grammatically correct as opposed to communicative competence? So long as people understand what you are saying, linguistic competence is irrelevant.